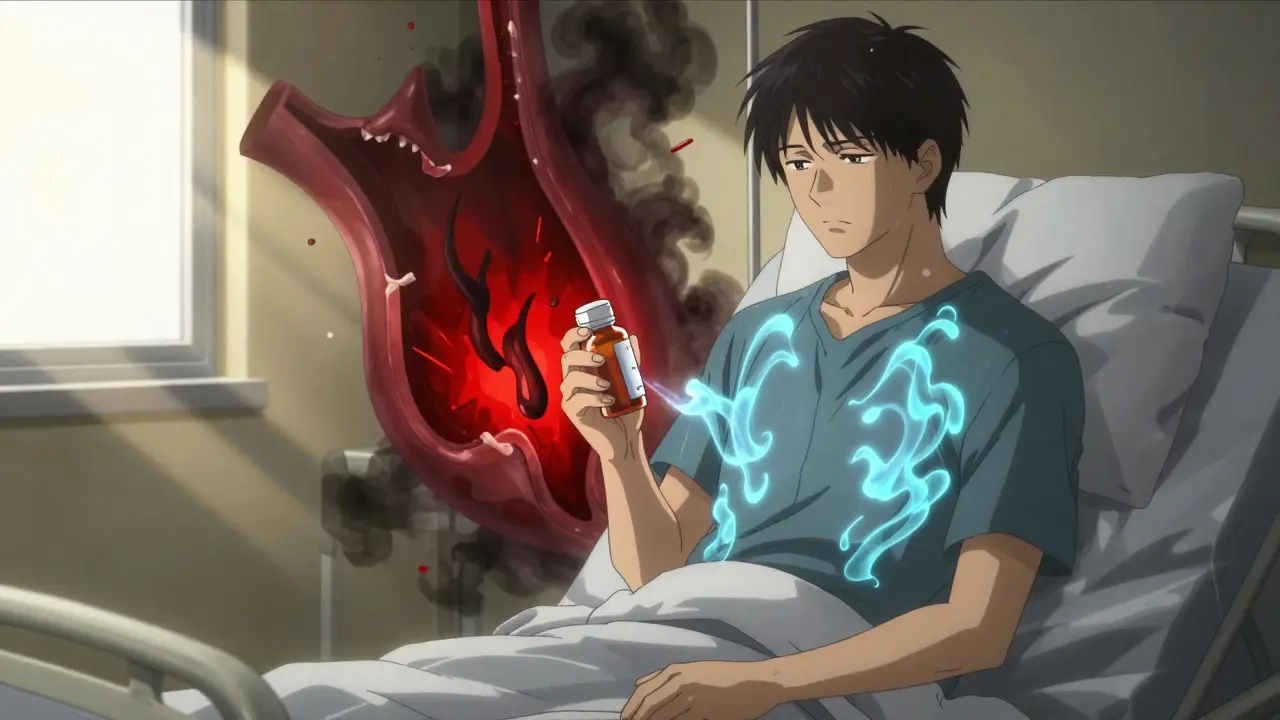

When your liver is damaged by cirrhosis, pressure builds up in the portal vein-the main blood vessel carrying blood from your intestines to your liver. This pressure forces blood to find new paths, creating swollen, fragile veins in your esophagus or stomach. These are called varices. When they rupture, it’s not just a bleed-it’s a medical emergency. About 1 in 5 people who experience variceal bleeding die within six weeks. But the good news? We know how to stop it, prevent it, and save lives-if we act fast and the right way.

What Happens During a Variceal Bleed?

Variceal bleeding doesn’t come with warning signs. One moment you’re fine; the next, you’re vomiting bright red blood or passing black, tarry stools. Some people feel dizzy, faint, or have a rapid heartbeat. It’s sudden, scary, and life-threatening. This isn’t a stomach ulcer or a hemorrhoid. This is bleeding from veins that are stretched thin by high pressure in the portal system-usually because of long-term liver damage from alcohol, hepatitis, or fatty liver disease.The key to survival? Acting within 12 hours. That’s the window where endoscopic treatment becomes most effective. Delay beyond that, and your chances of dying climb sharply. Hospitals with fast-response teams-gastroenterologists on call, ICU beds ready, blood products on standby-have survival rates nearly double those without.

Endoscopic Band Ligation: The Gold Standard

If you’re bleeding from varices, the first thing doctors do is reach for an endoscope. Not a scalpel. Not surgery. A thin, flexible tube with a camera and a tiny rubber band applicator. This is endoscopic band ligation (EBL).Here’s how it works: The endoscopist locates the swollen veins, grabs one with the device, and fires a small rubber band around its base. The band cuts off blood flow. The vein dies, shrinks, and eventually falls off. It’s not painful-you’re sedated-but afterward, you might feel throat soreness for a week or two. Some people struggle to swallow. Others feel fine by day three.

Success rates? Around 90-95% for stopping active bleeding. That’s better than any drug. And it’s why EBL replaced older methods like sclerotherapy (injecting chemicals to scar the veins) back in 2005. Sclerotherapy caused more complications-strictures, infections, perforations. Banding is cleaner, safer, faster.

But it’s not a one-time fix. You’ll need 3 to 4 sessions, spaced 1 to 2 weeks apart, to completely eliminate the varices. Each session costs between $1,200 and $1,800 in the U.S. But compared to the cost of ICU care after a rebleed-which can hit $50,000-it’s a bargain. High-volume centers that do over 50 banding procedures a year have 15% fewer rebleeds than low-volume ones. Experience matters.

Beta-Blockers: The Silent Shield

Banding stops the bleeding. But it doesn’t fix the root problem: high portal pressure. That’s where beta-blockers come in.Non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol and carvedilol reduce the force and volume of blood flowing into the portal system. They lower heart rate, reduce cardiac output, and shrink blood vessels in the gut. The goal? Cut portal pressure by at least 20% or bring it below 12 mmHg. That’s the threshold where varices are far less likely to rupture.

Propranolol is cheap-$4 to $10 a month. Carvedilol is pricier-$25 to $40-but it’s more effective. A 2021 study showed carvedilol lowers portal pressure by 22%, compared to 15% with propranolol. Both cut rebleeding risk in half. But here’s the catch: about 1 in 4 people can’t tolerate them. Side effects? Fatigue, dizziness, low blood pressure, slow heart rate. One patient on Reddit said propranolol left him too tired to get out of bed. He switched to carvedilol and felt better. But he still paid $35 a month out of pocket.

These drugs aren’t for everyone. If you have asthma, heart failure, or very low blood pressure, you can’t take them. Doctors start low-20 mg of propranolol twice a day, or 6.25 mg of carvedilol once a day-and slowly increase based on your heart rate and blood pressure. It takes weeks to reach the right dose. And even then, not everyone hits the target. Only 55% of patients in one VA study reached the full therapeutic dose within three months.

Prevention: Stopping the First Bleed

Most people with cirrhosis never bleed. But if you have large varices, your risk is high. That’s where prevention kicks in.For patients with medium-to-large varices and no prior bleed, guidelines now recommend starting carvedilol as first-line therapy. Why? Because it’s more effective than propranolol and doesn’t require multiple daily doses. In some cases, especially if you can’t tolerate beta-blockers, doctors may still recommend banding for primary prevention-but that’s debated. A 2023 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found carvedilol alone was just as good as banding at preventing the first bleed.

But prevention isn’t just drugs or banding. It’s also avoiding alcohol, controlling hepatitis B or C, managing diabetes, and losing weight if you have fatty liver disease. The liver doesn’t heal overnight. But stopping the damage gives your body a chance to stabilize.

When Banding and Beta-Blockers Aren’t Enough

Some patients don’t respond. Or they rebleed despite treatment. That’s when you need stronger options.For varices in the stomach (gastric varices), banding often fails. The solution? Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO). It’s a minimally invasive procedure where a radiologist threads a catheter into the vein, inflates a balloon, and injects glue to seal the varix. A 2023 study showed 30-day mortality dropped from 6.2% with banding alone to 2.8% when BRTO was added.

For high-risk patients-those with Child-Pugh B or C cirrhosis and active bleeding-transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is the most powerful tool. It creates a tunnel inside the liver to redirect blood flow, bypassing the high-pressure zone. One-year survival jumps from 61% with standard care to 86% with TIPS. But it comes with a cost: 30% of patients develop hepatic encephalopathy-brain fog, confusion, even coma-because toxins bypass the liver. So TIPS isn’t for everyone. Only 45% of U.S. hospitals can do it within 24 hours. And it’s not a cure. It’s a bridge.

The Real-World Challenges

Guidelines look perfect on paper. But reality is messier.Only 68% of patients get endoscopy within the critical 12-hour window. Emergency departments are busy. Endoscopists aren’t always on call. Delays cost lives.

And even when treatment is perfect, 65% of patients still rebleed within a year. That’s not failure-it’s the brutal truth of advanced liver disease. No treatment is 100%. That’s why patient support matters. The American Liver Foundation’s nurse navigator program helps 12,000 people a year coordinate care, find financial aid, and manage side effects. One patient wrote on a forum: “I dread the banding appointments every two weeks. But I know it’s saving my life.” That’s the emotional toll no guideline can measure.

What’s Next?

The future is coming. In 2023, the FDA approved a long-acting version of octreotide-a drug that reduces bleeding risk-that only needs monthly shots instead of daily infusions. That could help patients who struggle with adherence. And in 2024, the Baveno VIII meeting will likely confirm carvedilol as first-line for primary prevention, based on new data.Researchers are also testing AI tools that predict who’s most likely to bleed-using lab values, imaging, and even voice patterns. Early results suggest we might be able to spot risk weeks before a bleed happens. And new TIPS techniques, like percutaneous transsplenic access, could make the procedure available in 75% of U.S. hospitals by 2027, up from 45% now.

But the biggest gap isn’t technology. It’s access. Uninsured patients die from variceal bleeding at 35% higher rates than those with insurance. That’s not a medical problem. It’s a systemic one.

Variceal bleeding is preventable. Treatable. But only if you act fast, get the right care, and have the support to stick with it. Banding stops the bleed. Beta-blockers protect you from the next one. Prevention keeps you alive. And awareness? That’s what saves lives before the first drop of blood is even spilled.

gerard najera

January 1, 2026 AT 22:05Life’s fragile. One minute you’re fine, next you’re vomiting blood. No warning. Just pressure building silently inside you until it breaks. Banding works. Beta-blockers help. But what if your body just won’t cooperate? We treat symptoms like they’re the enemy. Maybe we should be asking why the system failed in the first place.

Stephen Gikuma

January 2, 2026 AT 10:01They don’t want you to know this, but banding is just the tip of the iceberg. Big Pharma pushed it because it’s repeatable. Beta-blockers? Cheap as dirt, but they don’t make billionaires. Meanwhile, TIPS? Only available in elite hospitals. That’s not medicine-that’s control. You think this is about health? It’s about who gets access. And guess who doesn’t? The poor. The uninsured. The ones who work two jobs just to breathe.

Bobby Collins

January 3, 2026 AT 19:15ok but what if the endoscope is dirty?? like i heard a nurse say once that some places reuse the same tube for like 3 patients and just wipe it off?? i mean… are we sure we’re not trading one death for another??

Layla Anna

January 5, 2026 AT 09:03my uncle had cirrhosis from hepatitis C… he was on propranolol for years and it saved him from bleeding twice 🥹 but he hated how tired it made him… he’d sit on the porch in the morning just staring at the birds… said it was the only time he felt calm. i wish more doctors asked how the meds made people feel, not just if their numbers looked good 💙

Heather Josey

January 6, 2026 AT 04:39This is an exceptionally well-researched and clinically accurate overview. The emphasis on timely endoscopy and the comparative efficacy of carvedilol versus propranolol aligns with current AASLD guidelines. I particularly appreciate the inclusion of real-world adherence challenges and the socioeconomic barriers to care. Healthcare systems must prioritize infrastructure investment-not just pharmacological innovation-to reduce preventable mortality. Thank you for this vital contribution.

Donna Peplinskie

January 6, 2026 AT 17:50I’ve worked in liver clinics for 18 years, and I’ve seen patients die because they couldn’t afford the $35 for carvedilol… or because the nearest endoscopy unit was 90 miles away… and they didn’t have a car… or because they were too ashamed to tell their family they drank too much… it’s not just about the medicine-it’s about the whole person. We need more community health workers, not more gadgets.

Olukayode Oguntulu

January 8, 2026 AT 12:36One must interrogate the epistemological foundations of this interventionist paradigm. The hegemony of endoscopic banding as the gold standard is a product of biomedical reductionism-a technocratic fetishization of proceduralism that obscures the ontological decay of the hepatic system. One cannot merely ligate varices while ignoring the metaphysical alienation wrought by late-stage capitalism’s commodification of corporeal suffering. The real pathology is not portal hypertension-it is the absence of solidarity.

jaspreet sandhu

January 9, 2026 AT 16:00Everyone talks about banding and beta-blockers like they’re magic, but in India, most people with cirrhosis don’t even get to see a doctor until they’re vomiting blood. No screening, no prevention, no nothing. And then you come here and act like everyone has access to a GI specialist on call? That’s not science, that’s privilege. And don’t even get me started on TIPS-half the hospitals here can’t even do a basic ultrasound right. You think your fancy stats matter when people are dying in waiting rooms because no one has time for them?

Alex Warden

January 11, 2026 AT 02:15Band ligation? That’s what we’re spending billions on? We’ve got better things to do. Why not just ban alcohol? Make hepatitis vaccines mandatory? Stop letting foreign doctors run our hospitals? This whole system is broken because we let bureaucrats and pharma lobbyists run things. Real Americans don’t need fancy tubes and expensive pills. We need discipline. Clean living. No handouts. Stop treating people like babies.

LIZETH DE PACHECO

January 11, 2026 AT 05:10Just wanted to say thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse in a rural ER, and I see these cases all the time. The fear in people’s eyes when they realize they’re bleeding inside… it stays with you. You’re right-it’s not just about the procedure. It’s about showing up for people when they’re at their worst. We’re doing better than we were 10 years ago, but we still have miles to go. Keep speaking up.

Lee M

January 11, 2026 AT 08:12There’s a deeper truth here: medicine treats symptoms because it can’t handle complexity. We band varices because it’s measurable. We prescribe beta-blockers because they’re quantifiable. But what about the grief? The shame? The loneliness of being told your body is broken because of choices you made decades ago? We don’t treat the soul. We treat the vessel. And that’s why people keep dying.

Kristen Russell

January 13, 2026 AT 00:21Carvedilol over propranolol-finally. Took long enough. And yes, BRTO for gastric varices? Absolute game-changer. I’ve seen patients go from ICU to home in 72 hours with it. This is what progress looks like: smarter tools, better data, less ego. Let’s stop arguing about who’s right and just do what works.

Matthew Hekmatniaz

January 14, 2026 AT 07:11My father had TIPS after two rebleeds. He got hepatic encephalopathy. Couldn’t remember my name for six months. But he lived. For three more years. We didn’t have insurance. We sold his truck. We slept in the hospital waiting room. He never complained. He just kept saying, ‘I’m glad I didn’t die in the ER.’ This isn’t about guidelines. It’s about love. And stubbornness. And showing up even when everything says to give up.

sharad vyas

January 15, 2026 AT 15:32In my village in Bihar, we used to treat liver sickness with neem leaves and turmeric paste. No endoscopy. No pills. Just patience. And community. People didn’t die alone in hospitals. They died in beds surrounded by family. Maybe the real cure isn’t in a catheter… but in remembering how to care for each other.