When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just rely on patents to keep competitors away. In fact, many drugs enjoy years of market protection without any patent at all. This is called regulatory exclusivity - a government-granted shield that stops generic or biosimilar versions from getting approved, even if the patent has expired. It’s not about who invented what. It’s about who got approved first. And it’s one of the biggest reasons why some drugs stay expensive for over a decade.

What Exactly Is Regulatory Exclusivity?

Regulatory exclusivity is a legal delay built into U.S. drug approval law. It’s not something a company applies for like a patent. It’s automatic. When the FDA approves a new drug and it meets certain criteria, the clock starts ticking on a period where no other company can get approval for a copy. This isn’t about stopping someone from making a similar drug - it’s about stopping them from using the original company’s clinical trial data to get their version approved faster. Think of it like this: developing a new drug takes 10-15 years and costs over $2 billion. The clinical trials? Those are expensive, risky, and time-consuming. Generic companies don’t have to repeat them. They can just reference the original data. Regulatory exclusivity says: “You can’t use that data for at least five, seven, or twelve years - depending on the drug.” It’s a trade-off. The government gives innovators a guaranteed window to recoup their investment. In return, the public gets faster access to cheaper versions later. But the length of that window? That’s where the fight begins.The Main Types of Exclusivity - And How Long They Last

Not all exclusivity is the same. The FDA grants different types based on what kind of drug it is. Here’s what you’ll actually see in practice:- New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity: 5 years. This is for drugs with a completely new active ingredient. For the first 4 years, the FDA won’t even accept an application for a generic version. At year 5, it can approve one - if there are no patents blocking it.

- Orphan drug exclusivity: 7 years. For drugs treating rare diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. This one is powerful. Even if a drug isn’t new, if it’s approved for a rare disease, it gets 7 years of protection. Over 47% of new drug approvals in 2023 were for orphan conditions.

- Biologics exclusivity: 12 years. This is the big one. Biologics - complex drugs made from living cells like Humira or Enbrel - get 12 years of exclusivity under the BPCIA law of 2009. No biosimilar can be approved during that time, no matter what.

- 3-year exclusivity: For new clinical studies that lead to a change in labeling, like a new use or dosage. This doesn’t block generics, but it does block copies that rely on that new data.

In Europe, it’s different. They use an “8+2+1” system: 8 years of data protection, then 2 more years where generics can’t be sold, and a possible extra year if the drug gets a new indication. Japan gives 10 years to new chemical drugs. The U.S. is among the longest in the world - especially for biologics.

Exclusivity vs. Patents - The Real Difference

People mix these up all the time. Here’s the key distinction:- Patents protect inventions - a specific molecule, formulation, or method of use. You have to file them, pay fees, and defend them in court. They can be challenged, invalidated, or worked around.

- Regulatory exclusivity protects the approval process. It doesn’t care about patents. It doesn’t care if someone invents a slightly different version. It just says: “You can’t use our data to get approved for X years.”

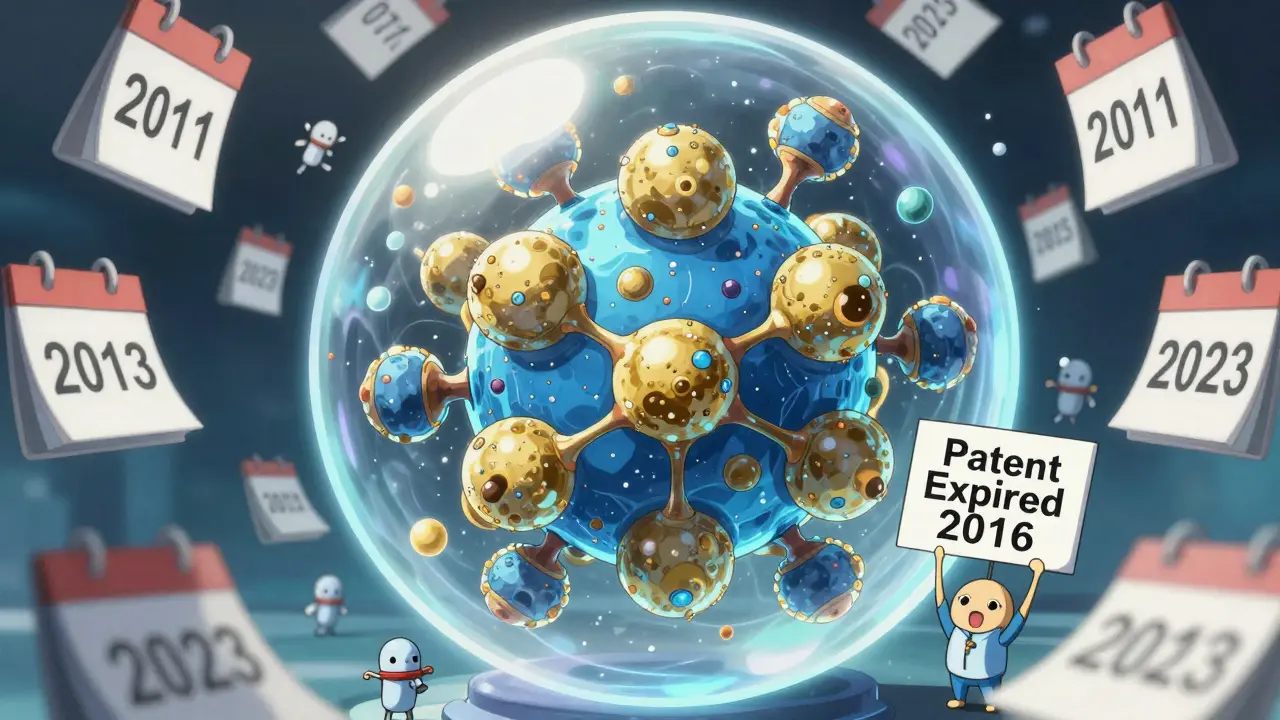

That’s why some drugs stay protected long after their patents expire. Take Humira (adalimumab). Its main patent expired in 2016. But because it’s a biologic, it had 12 years of regulatory exclusivity. That meant no biosimilar could be approved until 2023 - even though the patent was gone. In 2022, Humira made $19.9 billion in the U.S. alone.

Another example: a new chemical drug might get 5 years of exclusivity. But if it takes 7 years to get FDA approval, the patent could have already expired by the time the drug hits the market. Without regulatory exclusivity, the company would have zero protection. That’s why it’s called “non-patent market protection.” It fills the gap.

Who Benefits - And Who Gets Hurt?

The system was designed to encourage innovation. And it works - for some. Originator companies love it. A 2024 survey by the Association for Accessible Medicines found that 89% of big pharma firms say exclusivity is “essential” to recoup R&D costs. The FDA’s own data shows that, on average, a new drug enjoys 12.3 years of combined patent and exclusivity protection. For biologics? It’s 14.7 years. But generic manufacturers don’t. Only 42% of them are satisfied with how exclusivity is handled. Why? Because they’re stuck waiting. For NCEs, they can’t even submit their application for four years. That means spending millions on development without knowing if the FDA will ever approve it. For biologics, 12 years is a lifetime in drug development. Many generic companies call it “unfair.” And then there’s the price. Drugs under exclusivity cost 3.2 times more than generics, according to IQVIA. That’s why Public Citizen and other consumer groups argue exclusivity is being abused - especially for orphan drugs that cost hundreds of thousands per year. One drug, Zolgensma, costs over $2 million. It’s not patented. But it’s protected by orphan exclusivity. And no one else can copy it.How Companies Use Exclusivity Strategically

Big pharma doesn’t just sit back and wait. They game the system. One trick: “evergreening” through orphan designation. If a drug already exists for a common condition, a company might test it on a rare disease - even if it’s a tiny subset of patients. Suddenly, they get 7 extra years of protection. This isn’t rare. Over 1,000 drugs have received orphan status since 1983, many for conditions that affect fewer than 5,000 people. Another: stacking exclusivities. A new biologic might get 12 years. If it gets a new indication later, it can get an extra year. If it’s a combination product, the rules get even more complex. That’s why companies hire dedicated exclusivity managers - people whose only job is to track these dates across dozens of countries. Excelon IP says 73% of major pharma firms have at least one person focused solely on this. The FDA’s Purple Book is the official database for exclusivity status, but it’s incomplete. International data? Barely there. Companies have to build their own tracking systems - and they do.

What’s Changing? The Future of Exclusivity

Pressure is building to shorten exclusivity periods. In 2023, Congress proposed the “Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act” to cut biologics exclusivity from 12 to 10 years. It didn’t pass - big pharma lobbied hard. But the FDA’s 2024 Drug Competition Action Plan says it’s actively reviewing exclusivity rules to “better balance innovation and competition.” The European Union is moving even faster. Their 2023 reform proposal wants to cut data exclusivity from 8 to 6 years. Japan’s already shorter. The U.S. is an outlier. The Tufts Center for Drug Development predicts that by 2030, the average combined patent and exclusivity period will drop from 12.3 years to 10.8 years. Biologics will likely stay protected longer - but not forever. One thing’s clear: exclusivity isn’t going away. But it’s changing. And the next decade will decide whether it’s a tool for innovation - or a tool for price control.Why This Matters to You

If you or someone you know takes a brand-name drug - especially for cancer, autoimmune disease, or rare conditions - you’re living with the effects of regulatory exclusivity. It’s why your co-pay is high. Why your insurance denies a generic. Why you wait years for a cheaper version. It’s also why new treatments for rare diseases exist at all. Without exclusivity, companies wouldn’t risk developing drugs for conditions with so few patients. But that same protection can trap people in unaffordable care. The system isn’t broken. It’s designed exactly this way. The question is: is it still working for the people who need it most?Is regulatory exclusivity the same as a patent?

No. Patents protect inventions and are enforced by the patent holder in court. Regulatory exclusivity is granted automatically by the FDA and blocks competitors from using the original company’s clinical data to get approval. Exclusivity doesn’t require a patent - and can last even after a patent expires.

How long does regulatory exclusivity last?

It depends on the drug. New chemical entities get 5 years. Orphan drugs get 7 years. Biologics get 12 years. There’s also a 3-year exclusivity for new clinical data that changes a drug’s label. These periods start at FDA approval, not when the drug is invented.

Can a drug have both a patent and regulatory exclusivity?

Yes. Most new drugs have both. Patents protect the molecule or method, while exclusivity protects the approval process. They can run at the same time, and exclusivity often outlasts the patent - especially for biologics.

Why do generic companies complain about exclusivity?

Because they can’t start the approval process until the exclusivity period begins to wind down. For NCEs, they can’t even submit an application for 4 years. For biologics, they must wait 12 years - often spending millions developing a copy with no guarantee it’ll be approved. That increases risk and cost.

Is regulatory exclusivity the same around the world?

No. The U.S. has some of the longest terms - 12 years for biologics. The EU uses an 8+2+1 system. Japan gives 10 years to new chemical drugs. Some countries don’t have exclusivity at all. This affects where generics can launch and how fast prices drop globally.

Alexandra Enns

January 23, 2026 AT 16:03Let me break this down for you people who think patents are the only thing protecting drug prices - regulatory exclusivity is the real villain. The FDA just hands out 12-year monopolies like candy to Big Pharma while families go bankrupt paying for insulin. This isn’t innovation, it’s legalized theft. Canada does it better - we don’t let them stretch exclusivity like this. Shame on the U.S.

Marie-Pier D.

January 24, 2026 AT 02:46Thank you for writing this - seriously. I have a friend on Zolgensma and the cost broke our community fund. I didn’t realize it wasn’t even patented. Just... 7 years of exclusivity for a drug that helps 1 in a million babies? 🥺 We’re not punishing greed, we’re punishing kids. Please, someone fix this.

Himanshu Singh

January 25, 2026 AT 00:39It’s funny how we praise innovation but punish access. Exclusivity was meant to be a bridge - not a fortress. But when a company spends $2 billion to make a drug and then charges $2 million per dose, they’re not innovating… they’re extracting. The real question isn’t whether exclusivity should exist - it’s whether we’ve lost all moral compass in how we use it.

Jamie Hooper

January 26, 2026 AT 19:49so like… biologics get 12 yrs? lol. and we wonder why people go to canada for meds? 🤡 i mean, i get it, pharma needs to make money… but 12 years?? my aunt’s rheumatoid arthritis med cost more than my car. and its patent expired in 2016. so yeah. 12 yrs. yikes.

Don Foster

January 27, 2026 AT 21:32Look, if you can’t afford your meds then you shouldn’t have been born in America. The market rewards risk. If you want cheap drugs go live in India. Also, orphan drugs aren’t a loophole they’re a lifeline. Stop crying about capitalism

siva lingam

January 28, 2026 AT 00:1612 years for biologics? wow. what a surprise. the same companies that lobbied for this also made sure their CEOs got bonuses for every year the price stayed high. genius move. 🙃

Chloe Hadland

January 29, 2026 AT 17:34i just read this and felt so much better knowing this is why my co-pay is insane. i didn’t even know exclusivity existed. now i get why my insurance says no to generics. thanks for explaining it so clearly

Amelia Williams

January 30, 2026 AT 22:23What if we capped exclusivity at 8 years for all drugs? That’s still enough time to recoup R&D without turning life-saving meds into luxury items. Imagine if we redirected even 10% of the profits from those 12-year monopolies into subsidizing generics. We could make healthcare affordable without killing innovation. Let’s not choose between compassion and progress - we can have both.

Viola Li

January 31, 2026 AT 11:43People act like exclusivity is some evil scheme but without it no one would ever develop drugs for rare diseases. Zolgensma exists because of this system. If you want cheaper drugs, stop being a hypocrite and fund the research yourself. You don’t get free innovation without sacrifice.

Marlon Mentolaroc

February 1, 2026 AT 11:23Let’s be real - the FDA’s Purple Book is a mess. Companies spend millions just tracking exclusivity dates. That’s not innovation, that’s corporate tax evasion disguised as compliance. And the fact that we let them stack exclusivity like legos? That’s not policy - that’s a corporate game of Monopoly with human lives.

Gina Beard

February 2, 2026 AT 21:57Exclusivity isn’t the problem. The problem is that we treat medicine like a commodity instead of a right. The system works exactly as designed - to enrich shareholders, not save lives. We just stopped asking why.

Phil Maxwell

February 3, 2026 AT 06:42Yeah I’ve seen this play out with my dad’s biologic. Got approved in 2015, generics still not out. It’s wild how a single rule can hold back progress for a decade. I don’t know the answer but I know we’re all paying the price.