When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, you probably don’t think about how much the pharmacy actually gets paid for it. But that payment - the pharmacy reimbursement - is what keeps the doors open. And when a brand-name drug is swapped out for a generic, the money changes hands in ways that don’t always benefit the patient or the pharmacist. In fact, the system is designed to save money for insurers and PBMs, but often at the cost of pharmacy profitability, patient access, and true cost savings.

How Generic Substitution Works (And Why It’s Supposed to Save Money)

Generic drugs are chemically identical to their brand-name counterparts but cost far less. In 1993, only about one-third of prescriptions filled in the U.S. were generics. By 2023, that number jumped to over 90%, according to the Association for Accessible Medicines. That’s not just a trend - it’s a financial revolution. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that switching just seven classes of brand-name drugs to generics in Medicare could have saved $4 billion in 2007. Today, those savings are in the tens of billions. The idea is simple: replace expensive brand-name drugs with cheaper generics. But the way pharmacies get paid for that swap doesn’t always match the goal. The real story isn’t about the drug itself - it’s about the reimbursement model behind it.The Three Pillars of Pharmacy Reimbursement

Pharmacies don’t get paid a flat rate. Their reimbursement comes from three parts:- Ingredient cost: What the pharmacy paid for the drug

- Dispensing fee: A fixed amount for filling the prescription

- Reimbursement model: How the payer (insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, or PBM) calculates the total payment

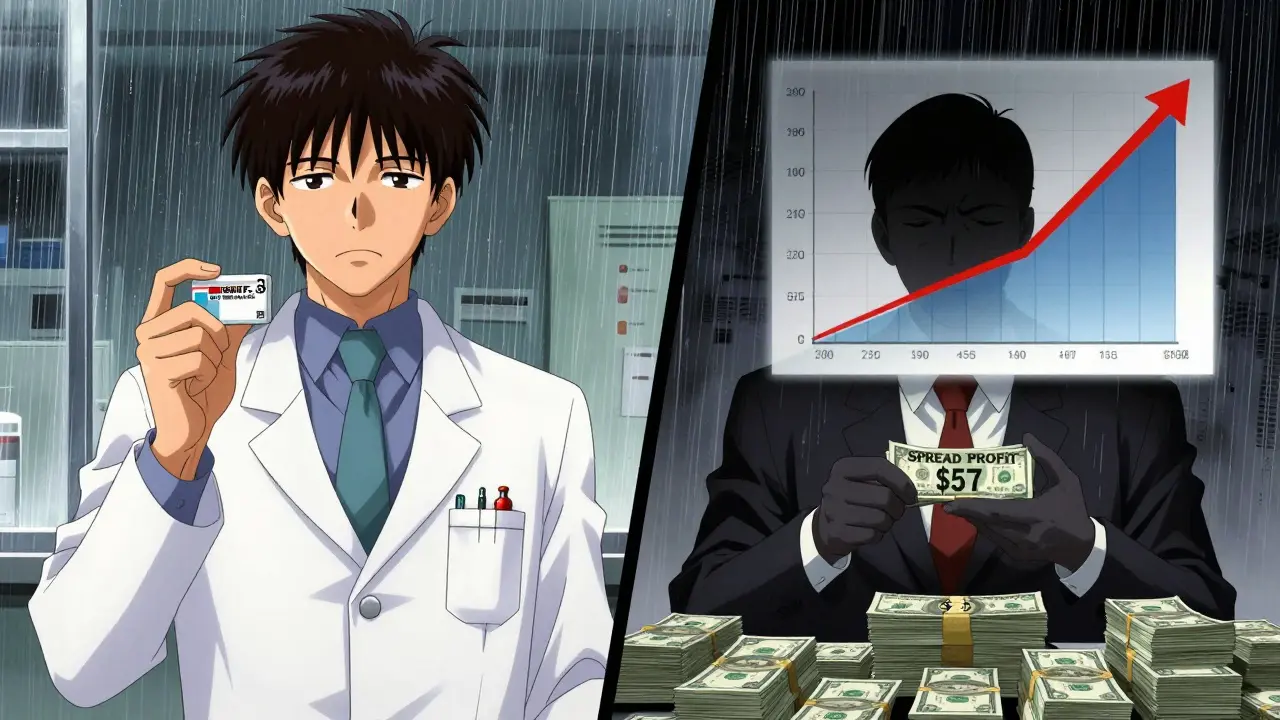

Spread Pricing: The Hidden Profit Engine

Spread pricing is the term for when a PBM charges the health plan one price for a drug but pays the pharmacy a lower price. The difference? That’s their profit. And it’s where generic substitution gets twisted. For example, a PBM might tell the insurance plan, “We’ll cover this generic at $15.” But they only pay the pharmacy $5 for it. The pharmacy gets $5 plus a $5 dispensing fee - so $10 total. The PBM keeps $5. That’s spread pricing. And it’s legal - as long as it’s hidden. Studies show that in some cases, the same generic drug - same manufacturer, same dose - was priced 20 times higher on MAC lists than its cheaper therapeutic alternative. Why? Because the PBM wanted to maximize spread. The patient didn’t care. The pharmacy didn’t know. The insurer paid more than they needed to. This isn’t theoretical. A 2022 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that when PBMs switched a patient from a $3 generic to a $60 generic - both equally effective - the PBM pocketed an extra $57 per prescription. The patient’s copay stayed the same. The pharmacy didn’t get more money. The only winner was the PBM.

Why Pharmacies Are Losing Money - Even When They Sell More Generics

You’d think more generics = more profit. But it’s not that simple. Gross margins on generics average 42.7%, compared to just 3.5% for brand-name drugs, according to the Commonwealth Fund. Sounds great, right? But here’s the reality:- Many pharmacies are paid based on MAC prices that are set below what they actually paid for the drug

- Dispensing fees haven’t kept up with inflation - some are still $4 or $5 after 20 years

- PBMs demand volume discounts, forcing pharmacies to buy in bulk, tying up cash flow

- When a pharmacy’s reimbursement drops below cost, they’re losing money on every generic they fill

Therapeutic Substitution: The Real Savings Opportunity

Most people think “generic substitution” means swapping one brand for its generic version. But the biggest savings come from therapeutic substitution: switching from a brand-name drug to a different generic drug in the same class. For example, instead of paying $120 for a brand-name statin, a patient could be switched to a generic statin that costs $4. That’s a 97% drop. But PBMs rarely push this. Why? Because therapeutic substitution requires clinical judgment. It’s not automatic. It’s not in the PBM’s algorithm. And it doesn’t create as much spread. The Congressional Budget Office found that therapeutic substitution saved far more than simple generic substitution. But the reimbursement system doesn’t reward it. It rewards volume - not value.What’s Changing? New Rules, New Pressure

The tide is turning - slowly. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 forced Medicare Part D to disclose drug pricing. That’s a start. Now, 15 states have created Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) that set Upper Payment Limits (UPLs). These caps force PBMs to lower MAC prices - which means pharmacies might finally get paid fairly. The Federal Trade Commission is also investigating PBM spread pricing. In 2023, they sent subpoenas to the three largest PBMs - CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx - demanding records on how they set MAC lists. If they’re found to be manipulating prices to boost profits, the rules could change. But here’s the problem: even if MAC lists get transparent, pharmacies still face a broken system. Dispensing fees are too low. Reimbursement delays are common. And PBMs still control the levers.

What This Means for Patients and Pharmacists

For patients: You might think you’re saving money because your copay is $5 for a generic. But if your insurer paid $60 for it and the pharmacy only got $5, you’re not seeing the real savings. Your premiums might still be rising because the system is rigged. For pharmacists: You’re the ones on the front lines. You’re the ones explaining why a patient got a different pill than expected. You’re the ones caught between a PBM’s secret pricing and a patient’s confusion. And you’re the ones getting squeezed out of business. The system was built to save money. But it’s saving money for the wrong people.What Can Be Done?

There are three clear paths forward:- Transparent MAC lists: PBMs must disclose how they set prices. No more secret spreads.

- Higher dispensing fees: Pay pharmacists fairly for their time. $5 in 2026 is not the same as $5 in 2006.

- Value-based reimbursement: Reward pharmacies for choosing the lowest-cost effective drug - not just any generic.

Paul Barnes

January 19, 2026 AT 18:28Pharmacies are getting screwed. The math is simple: if you pay $2.50 for a pill and get reimbursed $3, you’re losing money after rent, staff, and utilities. And no one talks about how PBMs set MAC prices like they’re running a casino. It’s not capitalism - it’s rent-seeking with a white coat.

Art Gar

January 21, 2026 AT 02:09It is, regrettably, an incontrovertible fact that the structural incentives embedded within the pharmaceutical benefit management ecosystem are fundamentally misaligned with the ethical imperatives of patient care and provider sustainability. The current reimbursement paradigm, predicated upon opaque spread pricing and arbitrary maximum allowable cost determinations, constitutes a systemic failure of fiduciary responsibility.

Edith Brederode

January 21, 2026 AT 20:49This is so infuriating 😤 I work at a small pharmacy and we just lost $180 last week on generics alone. We’re not greedy - we just need to cover our bills. Why does it feel like everyone’s making money except the people actually handing out the meds? 🙏

Arlene Mathison

January 23, 2026 AT 06:47Let’s be real - if we want real savings, we need to stop pretending generics are the magic fix. Therapeutic substitution is the real game-changer. Switching from a $120 brand to a $4 generic in the same class? That’s where the money’s at. But PBMs don’t care about that. They care about volume, not value. We need to reward pharmacists for making smart clinical choices, not just filling prescriptions.

And while we’re at it - raise the dispensing fee. $5 hasn’t changed since 2005. Inflation? What’s that? 😅

Independent pharmacies are dying because they’re being paid less than the cost of the pill. That’s not a business - that’s a charity with a cash register.

thomas wall

January 23, 2026 AT 11:12The erosion of professional autonomy in pharmacy is a tragedy of epic proportions. Once, pharmacists were trusted clinicians. Now, we are mere clerks executing algorithmic mandates dictated by corporate middlemen who have never held a prescription bottle. The MAC lists are not pricing tools - they are instruments of control. And the silent complicity of regulators? Unforgivable.

Jacob Cathro

January 23, 2026 AT 11:42so like… pbms are just middlemen who make money off the difference? and no one calls this out? 🤡 and the worst part? patients still pay the same copay even when the drug cost went from $3 to $60. i’m not even mad… i’m just impressed. like… wow. you really built a system where everyone loses except the guys in suits who don’t even know what a pill looks like. 🤦♂️

pragya mishra

January 25, 2026 AT 10:29Why don’t you people just demand transparency? If PBMs are hiding prices, sue them. If pharmacies are losing money, unionize. If patients are being misled, organize. Stop complaining on Reddit - take action. We have laws. Use them. Stop being passive.

clifford hoang

January 25, 2026 AT 20:22It’s all a psyop. The whole drug system is run by the deep state and Big Pharma to keep us docile. You think generics are about savings? Nah. They’re about tracking you. Every time you fill a script, your data gets fed into a global health AI that predicts your behavior. The MAC lists? They’re not about price - they’re about control. And the dispensing fee? That’s your biometric tax. 😈

They’re using your insulin prescriptions to build behavioral profiles. Wake up.

Emily Leigh

January 27, 2026 AT 10:25Wait… so the pharmacy gets paid less than they paid for the drug?? 😭 that’s not a business model - that’s a suicide pact. And they wonder why pharmacies are closing? DUH. Also - why do I still pay $5 for a $3 generic? Where’s my 97% savings?? I didn’t sign up for this. Someone explain this to me like I’m five. And why does no one else seem mad??

Carolyn Rose Meszaros

January 27, 2026 AT 20:51I just filled a script yesterday and the pharmacist looked exhausted. She said, ‘I hate this job sometimes.’ I didn’t know why… until now. 😔 Thanks for putting words to something I’ve felt but never understood. We need to fix this.

Renee Stringer

January 28, 2026 AT 12:51It’s morally indefensible that a system designed to reduce costs enriches intermediaries while impoverishing providers. This is not a market failure - it is a moral failure.

Nadia Watson

January 29, 2026 AT 07:25As someone who’s worked in community health for 20 years, I’ve seen pharmacies go from trusted neighborhood hubs to corporate warehouses. The loss of local pharmacies isn’t just economic - it’s cultural. People lose access to care, especially in rural areas. We need policy that values people over profit. Not just for patients - for the people who show up every day to help them.

Also - typo in the MAC section. ‘they paid’ should be ‘they pay’ - just saying, I care about the details 😊

Courtney Carra

January 30, 2026 AT 13:43It’s wild how we all blame the system… but no one ever asks: what if the real solution isn’t more regulation, but less PBM control? What if we just cut out the middleman and let pharmacies negotiate directly with insurers? No MAC lists. No spread pricing. Just fair prices and honest margins. Would it work? Maybe. But we’ll never try as long as the big three PBMs own the lobbyists.