Most people think generic drugs are cheap because they’re generic. But that’s not the whole story. Behind the scenes, insurers are using smart, aggressive buying tactics to drive generic drug prices down-sometimes by more than 90%. This isn’t luck. It’s bulk buying and tendering-a system designed to turn volume into power.

How Generic Drugs Became a Bargain

The modern generic drug market started in 1984 with the Hatch-Waxman Act. Before that, brand-name drugs had a monopoly. Afterward, companies could copy them once patents expired. The FDA approved the first generics quickly. But prices didn’t drop right away. That’s where insurers stepped in. By the early 2000s, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)-companies like OptumRx, Caremark, and Express Scripts-started managing drug benefits for insurers. They didn’t just negotiate prices. They created bidding wars. Instead of paying whatever a manufacturer charged, insurers would say: “We need 10 million pills of lisinopril. Who can do it cheapest?” The result? A single generic drug like metformin, used for diabetes, now costs under $5 for a 30-day supply in many cases. That’s down from over $50 a decade ago. The savings aren’t small. In 2023, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $445 billion. Nearly $200 billion of that came from adults aged 40 to 64.How Tendering Works: The Bidding Game

Tendering is simple in theory: invite multiple manufacturers to bid on a drug, pick the lowest, and lock in a contract. But it’s not just about price. Insurers set rules. They require minimum volume commitments. If a company wants the contract, they have to guarantee they can supply 5 million tablets a month. That forces manufacturers to run efficient, high-volume production lines. Lower costs. Lower prices. Insurers also use maximum allowable cost (MAC) lists. These are hidden price caps. If a generic drug costs more than the MAC, the insurer won’t pay more-even if the pharmacy charges it. That puts pressure on manufacturers to keep prices low. But here’s the catch: most plan sponsors don’t even see the MAC list. PBMs keep it secret. That’s how some high-priced generics still slip through.Why Some Generics Are Still Expensive

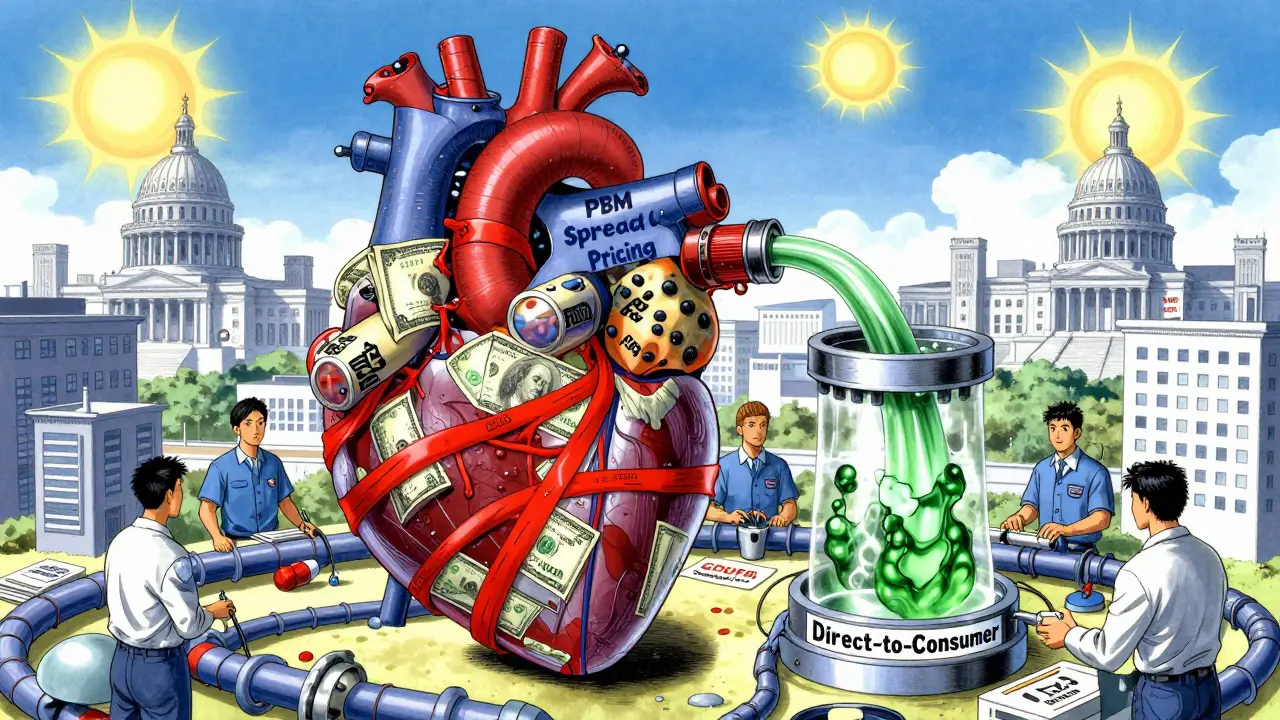

Not all generics are created equal. Some have dozens of manufacturers. Others? Just one or two. And that’s where the problem starts. Take albuterol inhalers. When prices got too low, manufacturers stopped making them. In 2020, 87% of hospitals reported shortages. Why? Because the cost to produce the inhaler was higher than what insurers were paying. The system broke. Even worse, some PBMs use a trick called spread pricing. They tell the insurer they paid $2 for a drug. They charge the pharmacy $8. The $6 difference? That’s their profit. The insurer thinks they’re saving money. But the patient still pays $20 out of pocket. And the generic? It’s not cheaper-it’s just hidden. A 2022 JAMA Network Open study found that some generics were costing more than others in the same class, not because of quality, but because of how they were placed on formularies. One drug might cost $12, another $48-same active ingredient, same dosage. The only difference? Which manufacturer paid the PBM the biggest rebate.

Transparent Pricing Is Changing the Game

Patients are catching on. And they’re going around the system. Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company started in 2022 with one store. By 2023, it had 35 locations across 12 states. Their model? No middlemen. No rebates. No spreads. They pay the wholesale price, add a 15% markup, and charge a flat $5 dispensing fee. A patient paid $87 for a generic blood pressure drug through insurance. At Cost Plus? $4.99. GoodRx and Blueberry Pharmacy are doing the same. Blueberry users give them 4.7 out of 5 stars. Why? Because they know exactly what they’ll pay. No surprises. No insurance loopholes. One reviewer wrote: “My blood pressure med costs exactly $15 a month. No insurance, no hassle.” And it’s not just individuals. Employers are switching. Navitus Health Solutions, a PBM that works with employers, reported 22% lower generic drug costs in 2023 compared to traditional PBMs. Why? They don’t hide pricing. They show it. And they let clients choose the lowest bidder.What Insurers Are Doing Right (and Wrong)

The best insurers don’t just sign contracts and forget. They audit. Quarterly. They look at which generics are costing the most. They check how many manufacturers make each drug. If only one company makes a drug, they start looking for alternatives-even if it’s a different brand name. They also push for first generics. The FDA found that the first company to launch a generic after a patent expires saves the system more than $1 billion in the first year. That’s because they’re the only option. But once others enter, prices crash. So insurers time their contracts to lock in those early savings. But many still get it wrong. Medicare Part D plans, for example, put generics on higher cost tiers than brand-name drugs. That’s backwards. Seven out of ten plans still do this. Why? Because PBMs get bigger rebates from brand-name makers. The system rewards higher prices. California tried to fix it with Senate Bill 17 in 2017. It forced PBMs to disclose any price difference between what they pay pharmacies and what insurers pay them-if it’s over 5%. Other states are following. Transparency is the only way to stop the game.

What You Can Do About It

You don’t need to be an insurer to save on generics. Here’s what works:- Always check GoodRx or SingleCare before using insurance. Many cash prices are lower than your copay.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is there a cheaper version of this drug?” Sometimes, a different manufacturer costs half as much.

- If you’re on Medicare, look into Medicare Part D plans that have low generic tiers. Not all are the same.

- Consider direct-to-consumer pharmacies like Cost Plus Drug Company if you take the same meds every month.

One user on Reddit said they saved $32 a month by ignoring their insurance and paying cash for three generics. That’s $384 a year. For someone on a fixed income, that’s a rent payment.

The Future: More Competition, More Savings

The FDA’s new GDUFA III rules, launched in 2023, are speeding up generic approvals. More manufacturers mean more competition. More competition means lower prices. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) just required Medicare Part D plans to show more pricing transparency in January 2024. That’s a big deal. If insurers can see how much PBMs are really charging, they’ll demand better deals. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that better tendering and more generics could save $127 billion over the next decade. That’s not theoretical. It’s already happening in places that cut out the middlemen. The lesson? Generics aren’t cheap because they’re simple. They’re cheap because someone fought for it. And that fight is still going.Why are some generic drugs more expensive than others if they’re the same medicine?

They’re not always the same. Different manufacturers use different inactive ingredients, packaging, or production methods. But often, the price difference comes from how PBMs structure their contracts. Some generics are placed on higher tiers because the manufacturer pays a bigger rebate to the PBM-not because the drug is better. Insurers may not even know they’re paying more for the same active ingredient.

Does using insurance always save money on generics?

No. Many people pay more through insurance than they would by paying cash. A 2023 study found that 97% of cash payments for prescriptions were for generics, even though cash payments made up only 4% of all prescriptions. That’s because insurance plans often have high copays or don’t cover certain generics well. Always compare your insurance price with GoodRx or Cost Plus Drug Company before filling a prescription.

What’s the difference between a PBM and an insurer?

Your insurer (like Blue Cross or UnitedHealthcare) pays for your health care. A pharmacy benefit manager (PBM)-like OptumRx or CVS Caremark-manages your drug benefits. They negotiate prices with pharmacies, set formularies, and decide which generics are covered. But PBMs often make money by keeping the difference between what they pay pharmacies and what insurers pay them. That’s called spread pricing. You’re not always saving money-you’re just paying differently.

Can generic drug shortages happen because of low prices?

Yes. When insurers push prices too low, manufacturers can’t make a profit. In 2020, albuterol inhalers disappeared from shelves because the price dropped below production cost. Eighty-seven percent of hospitals reported shortages. It’s a classic case of too much pressure. The system needs enough profit to keep manufacturers in the game, even if prices are low.

Are there any government programs that do this better than private insurers?

Yes. The Veterans Health Administration negotiates drug prices directly with manufacturers and pays about 24% less than Medicare Part D for the same generics. Medicare Part D itself has saved 80% on total drug prices since 2007, but it still uses PBMs with hidden pricing. The VA doesn’t use middlemen. It buys directly. That’s why it gets lower prices and fewer shortages.

Insurers aren’t saving money on generics by accident. They’re doing it through smart contracts, volume deals, and relentless competition. But the real winners? The people who know how to play the game-and when to walk away from it.