Headache & Neck Pain Symptom Checker

This interactive tool helps identify the most likely type of headache based on your reported symptoms. Select all symptoms you're experiencing:

Potential Headache Type:

Key Takeaways

- Neck muscles, spinal joints, and nerves often trigger or worsen headaches.

- Tension‑type and cervicogenic headaches are the most common neck‑related head pain.

- Accurate diagnosis combines symptom patterns with physical examination.

- Targeted physical therapy, posture correction, and gentle stretching can break the pain cycle.

- Early lifestyle tweaks often prevent chronic episodes.

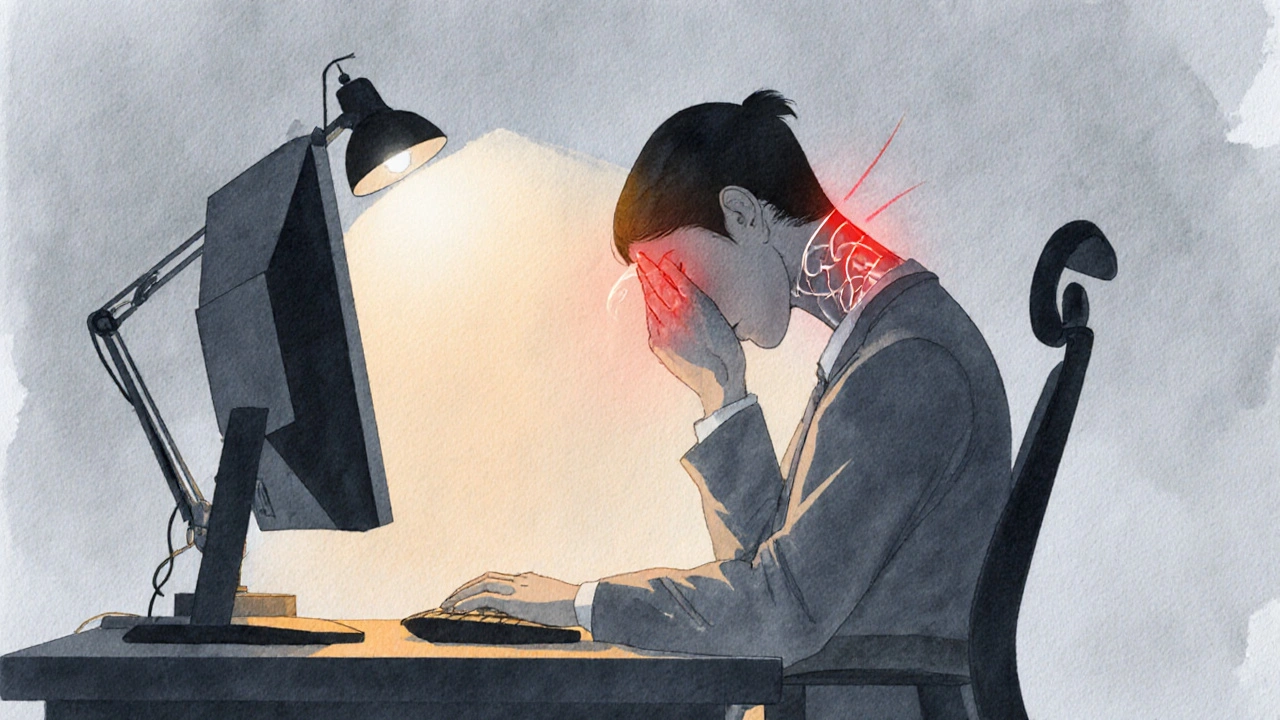

Ever wonder why a stiff morning neck seems to bring a pounding headache? You’re not alone. Millions of people experience this duo, yet the link between the two is often dismissed as “just stress.” In reality, the headaches and neck pain connection is rooted in anatomy, nerve pathways, and everyday habits. Understanding how the neck fuels head pain opens the door to smarter treatment and lasting relief.

How Headaches and Neck Pain Are Linked

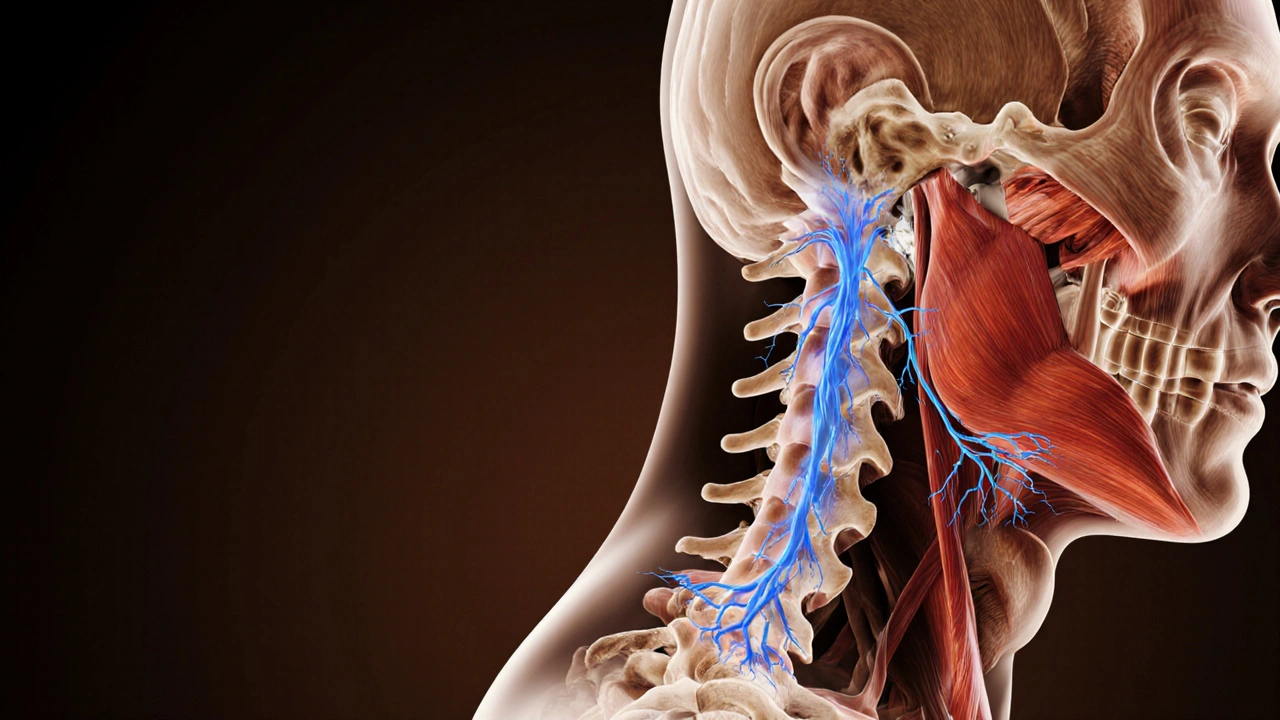

To see why the two complaints travel together, picture the cervical spine as a stack of seven vertebrae (C1‑C7) that support the head and protect the spinal cord. Muscles, ligaments, and facet joints surround these bones, allowing you to turn, nod, and keep your head upright. When any of these structures become tight, inflamed, or misaligned, they can irritate the occipital nerves that exit the spine and climb up to the scalp.

These nerves-especially the greater occipital nerve-carry sensations from the back of the head. If they’re compressed or irritated by a tight muscle (like the upper trapezius or suboccipital group), the brain interprets the signal as a headache. This phenomenon explains why a simple neck strain can feel like a full‑blown head ache.

Headache Types That Often Originate From the Neck

Not every headache that involves the neck is the same. Three main categories dominate clinical practice:

Tension‑type headache

These are the most common and usually present as a dull, band‑like pressure around the head. The pain often starts in the neck and shoulder muscles, spreading forward. Triggers include prolonged desk work, poor posture, and stress‑induced muscle clenching.

Cervicogenic headache

Unlike tension headaches, cervicogenic headaches stem directly from a specific neck joint or nerve problem. The pain typically begins at the base of the skull or one side of the neck and may radiate to the front of the head, eye, or temple. Certain neck movements-like turning the head to the affected side-exacerbate the pain.

Migraine with neck symptoms

While migraines are primarily a vascular and neurological disorder, many sufferers report neck stiffness or pain before the visual aura kicks in. The neck discomfort is thought to be a pre‑migraine warning sign, driven by central sensitization of pain pathways.

Why Neck Issues Trigger Headaches

Three mechanisms dominate the pain crossover:

- Muscle tension and trigger points: Tight muscles create “knots” that refer pain to the head. The suboccipital muscles, located just below the skull, are especially notorious for sending pain upward.

- Nerve irritation: The cervical nerves (C2‑C4) share pathways with the trigeminal nerve, the main conduit for head pain. When a cervical nerve is compressed, the brain may misinterpret the signal as a headache.

- Joint dysfunction: Facet joint arthritis or misalignment can alter how nerves glide, leading to chronic head pain.

Understanding which of these is at play helps clinicians tailor treatment-whether it’s massage for trigger points, nerve glides for irritation, or joint mobilization for facet dysfunction.

Diagnosing the Connection

A thorough evaluation starts with a detailed history: onset, location, aggravating factors, and any recent neck trauma. Clinicians then perform a physical exam that includes:

- Neck range‑of‑motion testing (looking for pain at specific angles).

- Palpation of trigger points in the upper trapezius, levator scapulae, and suboccipitals.

- Neurological screening for numbness or tingling that suggests nerve root involvement.

If red‑flag symptoms appear-such as sudden severe neck pain after a fall, fever, or unexplained weight loss-imaging (MRI or CT) may be ordered to rule out infection, tumor, or structural injury.

Treatment Options: From Self‑Care to Professional Help

Because the underlying cause varies, treatment is multimodal.

Self‑Care Strategies

- Heat or cold therapy: Applying a warm pack for 15 minutes can relax tight muscles, while an ice pack reduces inflammation after an acute strain.

- Gentle stretching: The “upper trapezius stretch” and “suboccipital release” performed twice daily lower tension.

- Over‑the‑counter pain relief: NSAIDs such as ibuprofen help curb inflammation, but should be used sparingly.

Physical therapy

Physical therapists teach targeted exercises that strengthen deep neck flexors, improve posture, and teach correct ergonomics. Manual techniques-like joint mobilization and myofascial release-directly address the sources of irritation.

Chiropractic and Osteopathic Care

Spinal adjustments aim to restore proper joint alignment, reducing nerve pinch points. While research shows mixed results, many patients report quick relief, especially for cervicogenic headaches.

Medication and Preventive Options

- Prescription muscle relaxants (e.g., cyclobenzaprine) for short‑term flare‑ups.

- Triptans for migraine‑related neck pain.

- Prophylactic beta‑blockers or antiepileptic drugs for chronic migraine sufferers.

When to Seek Specialist Care

If headaches persist beyond three weeks despite home measures, or if you notice neurological signs (numbness, weakness), see a neurologist or an ENT specialist. They can rule out other causes such as sinus disease or intracranial pathology.

Prevention: Keeping Your Neck and Head Happy

Most neck‑related headaches stem from everyday habits. Here are evidence‑backed habits that keep the pain cycle at bay:

- Ergonomic workstation: Position your monitor at eye level, keep the keyboard shoulder‑width apart, and use a chair that supports lumbar curvature.

- Frequent micro‑breaks: Every 30 minutes, stand, roll your shoulders, and perform a quick neck roll.

- Sleep support: Use a pillow that maintains neutral neck alignment-neither too high nor too flat.

- Stay active: Regular cardio improves blood flow, while yoga or Pilates enhances neck flexibility.

- Stress management: Mindfulness meditation reduces overall muscle tension, cutting down on tension‑type headaches.

Comparison of Common Neck‑Related Headache Types

| Type | Primary Cause | Neck Involvement | Typical Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tension‑type | Muscle tension & trigger points | Often bilateral, felt as a band around the head | Stretching, NSAIDs, stress reduction |

| Cervicogenic | Facet joint or nerve irritation | Unilateral pain starting at the base of skull | Physical therapy, manual joint mobilization, occasional nerve blocks |

| Migraine (with neck symptoms) | Neurovascular mechanisms, central sensitization | Neck stiffness often precedes aura; may be bilateral | Triptans, preventive meds, lifestyle triggers control |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a simple neck stretch really stop a headache?

Yes. Gentle stretches that target the suboccipital and upper trapezius muscles can release tension that’s feeding the pain. Most people feel relief within 10‑15 minutes if the headache is tension‑type.

How do I know if my headache is cervicogenic?

Key clues include pain that starts at the back of the head or neck, worsens with specific neck movements, and is mostly one‑sided. A clinician can confirm with a neck‑range‑of‑motion test and by reproducing the pain through palpation.

Is it safe to use over‑the‑counter painkillers every day?

Occasional use is fine, but daily use can lead to stomach irritation, kidney strain, or rebound headaches. Talk to a healthcare provider if you need medication more than a few times a week.

Can poor posture at my desk cause chronic headaches?

Absolutely. Slouching shortens the chest muscles and over‑activates neck extensors, creating a constant pull on the cervical spine. Over time this tension can radiate upward as a headache.

When should I see a doctor for neck‑related headaches?

If the pain is severe, lasts longer than three weeks, or is accompanied by neurological signs (numbness, weakness, vision changes), seek medical attention promptly. These symptoms could signal a more serious underlying condition.

OKORIE JOSEPH

October 7, 2025 AT 17:13Stop ignoring the neck when you get a headache it’s a clear sign you’re slouching all day

Lucy Pittendreigh

October 7, 2025 AT 18:36Thinking a headache is just “stress” shows you’re ignoring the real issue it’s a sign of poor spinal health. You can’t keep blaming random factors when the neck is the source. Adjust your ergonomics now.

Nikita Warner

October 7, 2025 AT 20:00The relationship between cervical tension and cephalic pain is well documented in clinical literature. When the upper trapezius and suboccipital muscles become chronically shortened, they generate nociceptive input that converges on the trigeminocervical nucleus. This convergence explains why patients often report a band‑like pressure around the head that intensifies with neck flexion. Assessing neck range of motion in multiple planes allows the practitioner to identify specific movement‑provoking patterns. Palpation of trigger points in the levator scapulae can uncover referred pain that mimics tension‑type headache. Imaging is generally reserved for cases with red‑flag symptoms such as sudden onset after trauma or neurological deficits. For most individuals, a structured home program focusing on cervical flexor strengthening yields significant improvement. Exercises such as chin tucks performed in four sets of ten repetitions multiple times per day restore muscular balance. Complementary modalities including myofascial release and gentle joint mobilizations further reduce proprioceptive distortion. Patients should be educated about ergonomics, ensuring that monitor height aligns with eye level to avoid forward head posture. Regular micro‑breaks every thirty minutes, consisting of shoulder rolls and neck rotations, prevent muscle fatigue. In cases where conservative measures fail, targeted nerve blocks or botulinum toxin injections may be considered under specialist supervision. Pharmacologic therapy, limited to short courses of non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs, can assist during acute flare‑ups. Lifestyle modifications such as adequate hydration, balanced sleep hygiene, and stress management are integral to long‑term success. Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach combining physical therapy, behavioral strategies, and, when necessary, medical intervention offers the most reliable path to relief.

Liam Mahoney

October 7, 2025 AT 21:23Look, if you’re not willing to straighten up you’re basically inviting pain. It’s not rocket science just sit tall and move. Stop making excuses.

Anna Österlund

October 7, 2025 AT 22:46Great article! I love the practical tips. Keep it up.

Brian Lancaster-Mayzure

October 8, 2025 AT 00:10Really appreciate the focus on posture and gentle stretches. I’ve found that a few minutes of neck rolls each hour makes a huge difference for my own tension. Thanks for sharing.

Erynn Rhode

October 8, 2025 AT 01:33As someone who constantly battles both neck stiffness and chronic migraines, I find the blend of self‑care and professional advice in this piece to be spot‑on. The suggestion to combine heat therapy with targeted sub‑occipital releases aligns perfectly with what my physio recommended, and I’ve noticed a measurable reduction in headache frequency over the past month. Also, the reminder about using a supportive pillow cannot be overstated – it’s a game‑changer for sleep quality 😃. While over‑the‑counter NSAIDs can provide temporary relief, they should never replace a structured rehab routine. My personal protocol now includes a daily 10‑minute stretch series, ergonomic desk adjustments, and a brief mindfulness session before bed. Consistency is key; the benefits compound over time. If you’re still experiencing persistent pain despite these steps, it’s wise to seek a specialist evaluation to rule out underlying pathology. Overall, the article does an excellent job of demystifying the neck‑head connection and offering actionable steps.

Rhys Black

October 8, 2025 AT 02:56One cannot merely skim the surface of cervical dynamics without acknowledging the profound symphony of fascia, nerve, and bone that orchestrates our very perception of pain. To trivialize this intricate ballet as “just posture” is an affront to the elegance of human anatomy. The article rises above such reductive sentiment, presenting a nuanced exploration worthy of scholarly admiration. Its eloquence beckons the reader to transcend complacency and engage in intentional movement. Bravo to the author for melding scientific rigor with accessible prose.

Abhishek A Mishra

October 8, 2025 AT 04:20Hey there, love the vibe of the post! Just a little heads up – “cervicogenic” is spelled with a ‘c’ not a ‘s’, and don’t forget a space after commas. Keep the good info coming.

Jaylynn Bachant

October 8, 2025 AT 05:43In the hollow of every ache lies a whisper of existence, a reminder that the body is a parchment upon which the universe writes its riddles.

Anuj Ariyo

October 8, 2025 AT 07:06Nice overview, very clear. It tells you what to do, why it matters, and how to start. Simple and direct.

Tom Lane

October 8, 2025 AT 08:30Awesome breakdown! If you keep up with the stretches and posture checks, you’ll see real results fast. Let’s stay motivated and crush those headaches together.

Darlene Young

October 8, 2025 AT 09:53Whoa, the colors of this guide paint a vivid picture of relief. I love how it blends science with soul‑soothing advice, turning a dull medical topic into a kaleidoscope of hope.

Kayla Rayburn

October 8, 2025 AT 11:16You’ve got this! Stick to the routine, celebrate small wins, and remember that consistency beats intensity every time.

Dina Mohamed

October 8, 2025 AT 12:40What a fantastic read, truly! The steps are clear, the tone is encouraging, and the science is solid, making it easy to adopt new habits, stay motivated, and feel empowered, every single day.