Climate Diarrhea Risk Estimator

This tool estimates the potential increase in acute diarrhea cases based on climate conditions. Enter your location's average annual temperature and rainfall to see projected risk changes.

Estimated Impact

Enter your climate data and click "Estimate Diarrhea Risk" to see projected changes in acute diarrhea cases.

When extreme heat, heavy rains, and rising sea levels start messing with the places we get our water and food, the result is often a spike in stomach‑upset cases that many folks brush off as "just a bad day." In reality, the surge in acute diarrhea is a direct symptom of a warming planet, and it’s dragging down health outcomes for millions, especially in low‑resource settings.

Acute Diarrhea is a rapid‑onset condition marked by frequent, watery stools, usually caused by waterborne pathogens such as rotavirus, E. coli, and cholera bacteria. It accounts for roughly 1.7 million deaths each year, mostly among children under five, according to the World Health Organization.

Climate Change refers to long‑term shifts in temperature, precipitation patterns, and the frequency of extreme weather events driven by greenhouse‑gas emissions creates the perfect breeding ground for these germs. Higher temperatures speed up bacterial growth, while floods and droughts disrupt water and sanitation systems, forcing people to drink contaminated water.

Key Takeaways

- Rising temps and erratic rainfall boost pathogen survival, leading to more acute‑diarrhea outbreaks.

- Children under five, refugees, and those living in slums face the highest risk.

- Global incidence could climb by 30‑40% by 2050 if no climate‑smart interventions are adopted.

- Strengthening water‑sanitation‑hygiene (WASH) infrastructure and climate‑resilient health systems cuts deaths dramatically.

- International bodies like the WHO and UNICEF are pushing integrated action plans, but funding gaps remain.

Why a Hotter World Means More Diarrhea

Heat isn’t just uncomfortable-it’s a catalyst for microbes. Temperature Rise accelerates the replication cycle of bacteria such as Vibrio cholerae and the protozoan Giardia, shortening the time it takes for contaminants to become infectious.

Heavy rainfall and Flooding overwhelms sewage treatment plants, pushes untreated waste into drinking‑water sources, and creates standing water where insects can breed all mix together. In 2023, floods in Bangladesh contaminated over 4 million liters of municipal water, sparking a two‑week diarrheal surge that claimed 180 lives.

Drought, on the other hand, concentrates pathogens in shrinking water bodies. When people resort to unsafe wells, exposure spikes. A 2022 case‑control study in Ethiopia found a 2.8‑fold increase in acute‑diarrhea cases during a prolonged drought season.

Who Gets Hit the Hardest?

The burden isn’t spread evenly. Children under five lose the most because their immune systems are still developing, and dehydration hits them faster. In sub‑Saharan Africa, acute diarrhea accounts for 15% of all deaths in this age group.

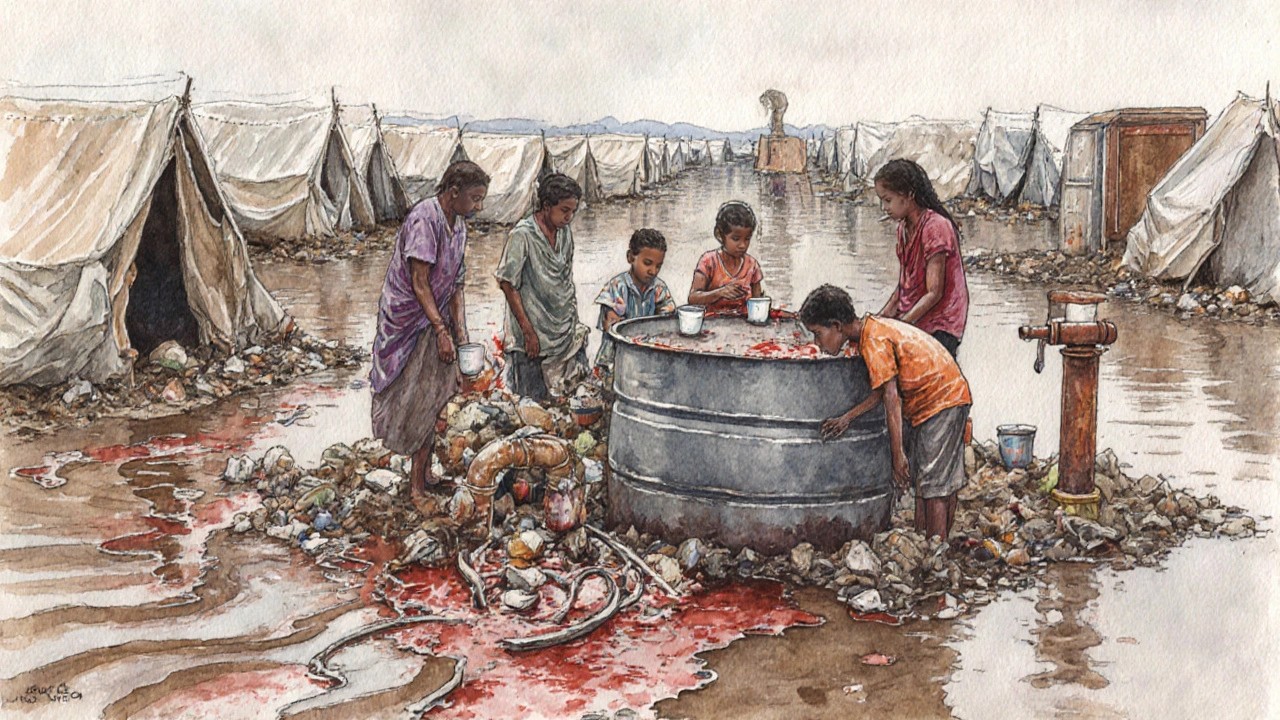

Refugee camps and informal settlements also sit on the frontline. Overcrowding, limited sanitation, and reliance on makeshift water sources mean a single outbreak can affect thousands within days. The UNHCR reported that a cholera outbreak in a Syrian camp in 2021 infected 3,500 people in just three weeks.

Older adults with chronic illnesses and malnutrition are another vulnerable slice. Malnutrition weakens gut barriers, making it easier for pathogens to cause severe disease.

Numbers That Tell the Story

Data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study shows a clear upward trend. In 2000, the age‑standardized incidence of acute diarrhea was 1,200 cases per 100,000 people. By 2022, that figure rose to 1,560, a 30% jump. climate change acute diarrhea projections from the WHO’s Climate‑Health Modeling Initiative suggest a further 25‑40% rise by 2050 under a high‑emission scenario.

Regional differences are stark. The table below highlights three hotspots and their observed versus projected rates:

| Region | 2022 | 2050 (High‑Emission) | Key Climate Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Asia | 1,800 | 2,550 | Monsoon flooding + heatwaves |

| Sub‑Saharan Africa | 1,650 | 2,300 | Drought‑induced water scarcity |

| Latin America & Caribbean | 1,200 | 1,620 | Extreme rainfall events |

The Role of Water‑borne Pathogens and Sanitation

When climate extremes strike, Waterborne Pathogens such as rotavirus, norovirus, and Shigella thrive in contaminated water and food they become the main culprits of acute diarrhea. The “chain of infection” shortens because people often lack safe storage options.

Sanitation Infrastructure includes latrines, sewage treatment plants, and drainage systems that prevent fecal matter from entering drinking water is the break in that chain. Yet climate‑stress tests reveal many facilities crumble under flood loads or lack power for operation during heat waves.

Investing in climate‑resilient WASH (Water‑Sanitation‑Hygiene) systems-like sealed latrine pits, solar‑powered pumps, and portable water‑purification units-has shown a 45% reduction in diarrheal cases in pilot projects in Kenya and Vietnam.

Health‑System Strain and Response Gaps

Acute diarrhea may seem like a simple disease, but severe cases demand rehydration therapy, intravenous fluids, and sometimes antibiotics. In climate‑driven spikes, hospitals quickly run out of oral rehydration salts (ORS) and trained staff.

World Health Organization (WHO) sets global guidelines for diarrheal disease management and emergency response recommends a three‑tiered approach: community‑level ORS distribution, rapid triage at health posts, and referral hospitals for severe dehydration. However, many low‑income countries lack the logistics to move supplies after a flood.

Training community health workers to recognize dehydration signs and administer ORS can save lives. In a 2021 program in Nepal, death rates fell from 2.4% to 0.6% during monsoon‑related outbreaks.

Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies

There are two levers to cut the diarrheal toll: curb climate change itself and adapt to its unavoidable impacts.

On the mitigation side, cutting methane and CO₂ emissions reduces future temperature spikes, directly lowering pathogen growth rates. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) models show that limiting warming to 1.5°C could prevent up to 200,000 diarrheal deaths annually by 2100.

Adaptation measures are more immediate:

- Early‑warning systems: Use satellite data to forecast flood‑related contamination and alert communities.

- Resilient water sources: Build raised, protected wells and rainwater harvesting tanks with filtration.

- Community education: Teach safe hand‑washing, proper food storage, and how to treat water with chlorine tablets.

- Stockpiling ORS: Maintain buffer supplies in flood‑prone districts.

Global Policy Landscape

International agencies are aligning climate and health agendas. UNICEF focuses on child health, nutrition, and WASH programs in climate‑vulnerable regions launched the “Water+Health” initiative in 2022, targeting 30 million children by 2027.

The WHO’s “Global Climate and Health Alliance” includes 45 member states committed to integrating climate risk assessments into national health plans. Funding remains a hurdle-only 12% of the $300billion pledged for climate‑resilient health infrastructure has been disbursed.

Practical Steps for Communities and Individuals

Even without massive infrastructure, small actions can curb outbreaks:

- Boil water for at least one minute after a flood, or use chlorine tablets (2mg per liter).

- Wash hands with soap and clean water before eating or preparing food.

- Store ORS packets in a dry, cool place and replace them annually.

- Set up a community “diarrhea watch” board where members report symptoms early.

- Participate in local climate‑adaptation meetings to voice water‑safety concerns.

When these habits become routine, the collective risk drops dramatically, even if the climate continues to shift.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does hot weather increase diarrhea cases?

Higher temperatures speed up the growth of bacteria and parasites in water and food, making contamination more likely. Heat also encourages people to store water in open containers, which can become breeding grounds for microbes.

How can floods cause diarrhea outbreaks?

Floods overwhelm sewage systems, mixing human waste with drinking water. When people consume that water or food washed with it, they ingest the pathogens that cause acute diarrhea.

What is the most effective way to treat acute diarrhea at home?

Rehydration is key. Use oral rehydration salts (ORS) mixed with clean water-about one packet per liter-and sip frequently. Continue feeding light, bland foods; avoid sugary or fatty drinks.

Can climate‑smart agriculture reduce diarrheal disease?

Yes. Practices like drip irrigation and protected seedling beds limit water stagnation, reducing the spread of water‑borne pathogens from fields to households.

What role do international agencies play?

Organizations such as WHO and UNICEF coordinate research, set treatment guidelines, fund WASH projects, and help countries develop climate‑resilient health policies.

Anshul Gupta

October 4, 2025 AT 12:50Another doomsday article that pretends climate change is the sole villain of diarrhea, ignoring basic hygiene failures.

Sure, the planet is warming, but if people can't wash their hands, the disease burden stays high.

Maryanne robinson

October 4, 2025 AT 13:06Thank you for sharing this comprehensive overview of how climate dynamics intersect with diarrheal disease.

The data you presented makes it clear that rising temperatures are not just uncomfortable but actively accelerate pathogen replication.

For instance, the increased growth rates of Vibrio cholerae in warmer waters translate directly into higher infection chances for nearby communities.

Your illustration of flood‑driven sewage overload in Bangladesh offers a stark, real‑world example of the mechanism you describe.

Equally important is the drought scenario you highlighted in Ethiopia, where shrinking water sources concentrate harmful microbes.

The numbers you cited-30 % rise in global incidence since 2000 and projected 25‑40 % increase by 2050-are alarming and demand urgent policy attention.

I especially appreciate the emphasis on water‑sanitation‑hygiene (WASH) infrastructure as a lever that can cut diarrheal deaths by nearly half in pilot projects.

The solar‑powered pumps and sealed latrine pits you mentioned are practical, low‑cost solutions that can be scaled with the right financing.

Moreover, integrating early‑warning satellite systems with community health alerts could dramatically reduce exposure during flood events.

It is promising to see UNICEF’s “Water+Health” initiative aiming to protect 30 million children by 2027, though the funding gap remains a major hurdle.

The WHO’s Global Climate and Health Alliance is another critical platform, but translating commitments into on‑the‑ground resources is essential.

From a public‑health perspective, training community health workers to administer oral rehydration salts (ORS) during crises can save thousands of lives, as demonstrated in Nepal.

Your call for climate‑smart agriculture, such as drip irrigation, underscores that preventing contamination at the source is just as vital as treatment.

In addition, encouraging households to adopt simple practices-boiling water, using chlorine tablets, proper hand‑washing-remains a cost‑effective line of defense.

Overall, your article stitches together the science, the statistics, and the actionable steps in a way that policymakers can actually use.

Let’s hope that interdisciplinary collaborations continue to bridge climate research and global health to keep these preventable deaths in check.

Erika Ponce

October 4, 2025 AT 13:23I think the post does a good job explaining the link between climate and diarrhea, even if some of the numbers feel a bit overwhelming.

but its really eye opening.

Danny de Zayas

October 4, 2025 AT 13:40Looks like we need more robust water systems, especially in places that get hit by both floods and droughts.

John Vallee

October 4, 2025 AT 13:56Bravo! This piece ties together climate science and public health with the flair of a blockbuster documentary.

It reads like a wake‑up call, yet it also hands us a toolbox of interventions-early‑warning alerts, solar‑powered pumps, community‑led ORS distribution-all laid out with cinematic clarity.

The sheer breadth from pathogen biology to policy frameworks is impressive, and the call for integrated funding hits home.

Honestly, it's the kind of article that should be on every climate‑health briefing deck.

Brian Davis

October 4, 2025 AT 14:13From a cultural standpoint, it's fascinating how climate‑induced health threats can reshape community rituals around water collection.

In many societies, gathering water is a social activity, and when that water becomes unsafe, it disrupts not only health but also social cohesion.

Investing in resilient water infrastructure therefore preserves both physical well‑being and cultural continuity.

jenni williams

October 4, 2025 AT 14:30Thanks for breaking it down so simply 😊

Even small steps like boiling water after a flood can make a huge difference for families.

Kevin Galligan

October 4, 2025 AT 14:46Great, another reminder that the planet is heating up and we’ll all be sipping contaminated broth tomorrow.

Just what I needed to spice up my day.

Dileep Jha

October 4, 2025 AT 15:03While your hyperbolic framing is noted, the etiological cascade can be modeled via stochastic differential equations that account for hydrological perturbations, pathogen load variance, and host susceptibility indices, thereby quantifying risk more rigorously than anecdotal lamentation.

Michael Dennis

October 4, 2025 AT 15:20Although the article presents compelling data, it fails to address the underlying socioeconomic determinants that perpetuate diarrheal disease cycles in vulnerable regions.

Blair Robertshaw

October 4, 2025 AT 15:36Wow, drop the pomp, Michael. It’s obvious you’re just looking for a fault in any decent research.

Alec Maley

October 4, 2025 AT 15:53Totally agree – we need action now.