Glaucoma Risk Calculator

Assess Your Glaucoma Risk

This tool helps estimate your risk of developing glaucoma based on your eye inflammation type and other factors. Please provide the required information below.

Risk Assessment Result

Key Takeaways

- Inflammation inside the eye can raise intraocular pressure, a major trigger for glaucoma.

- Uveitis is the most common type of eye inflammation linked to secondary glaucoma.

- Prompt diagnosis and anti‑inflammatory treatment dramatically lower the risk of permanent vision loss.

- Eye‑drop medications, laser therapy, and surgery are options when pressure stays high.

- Lifestyle habits-regular eye exams, protecting eyes from injury, and managing systemic autoimmune disease-help keep both conditions in check.

When talking about eye health, Glaucoma is a group of eye disorders that damage the optic nerve, often because of elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). While most people associate glaucoma with a silent, age‑related rise in pressure, a less‑known driver is inflammation inside the eye. This article explains how eye inflammation refers to any swelling of ocular tissues, most often uveitis can set off the cascade that leads to glaucoma, what signs to watch for, and how doctors break the cycle.

What Exactly Is Eye Inflammation?

Eye inflammation, medically called uveitis the inflammation of the uveal tract, which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid, comes in several flavors:

- Anterior uveitis: Affects the front of the eye (iris and ciliary body). It’s the most common and often causes redness, pain, and light sensitivity.

- Intermediate uveitis: Involves the vitreous humor, producing floaters and blurry vision.

- Posterior uveitis: Hits the retina or choroid, leading to visual distortion.

- Panuveitis: Inflammation spreads across all layers.

Triggers range from infections (e.g., toxoplasmosis, herpes) to systemic autoimmune conditions like sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. Even trauma or certain medications can provoke an inflammatory response.

How Inflammation Can Lead to Glaucoma

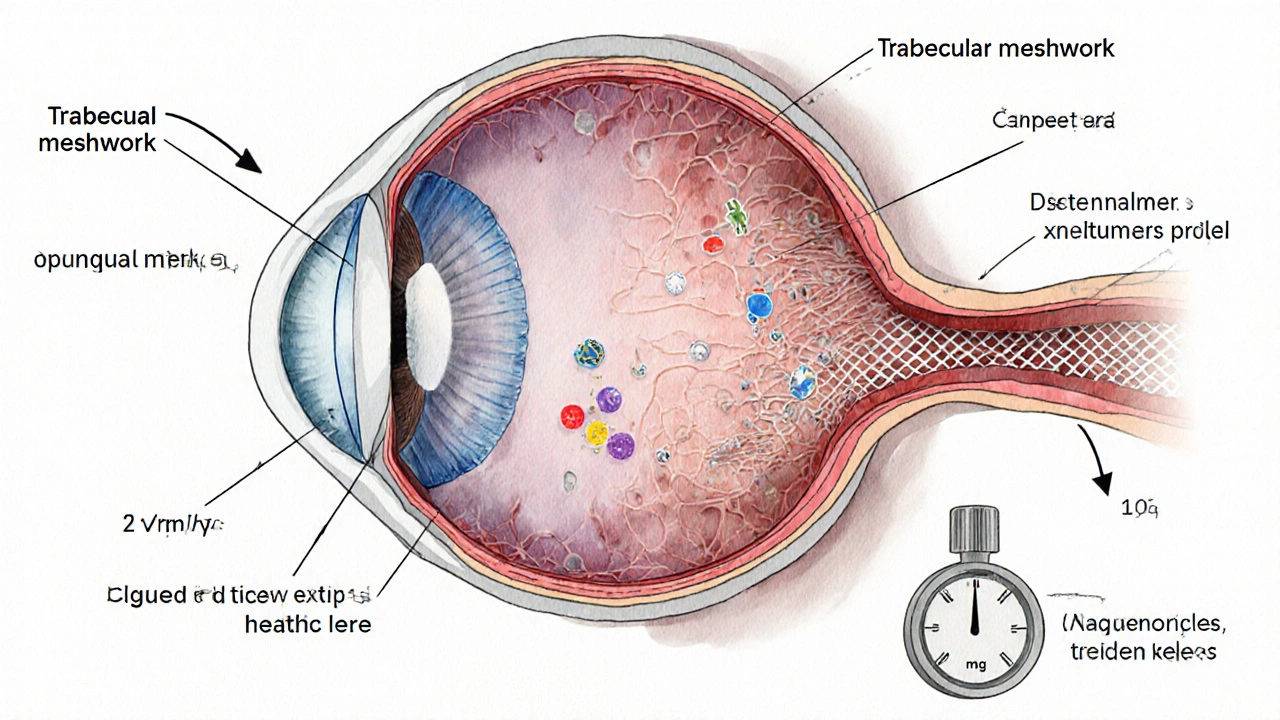

Inflammation raises IOP through several mechanisms. Think of the eye as a pressure‑regulated balloon: fluid (aqueous humor) circulates from the ciliary body, passes through the trabecular meshwork a spongy tissue at the eye’s drainage angle, and exits via Schlemm’s canal. When inflammation swells this drainage pathway, flow slows, pressure climbs, and the optic nerve gets squeezed.

Key pathways include:

- Cellular debris: Inflammatory cells and proteins clog the trabecular meshwork.

- Cytokine release: Molecules like tumor necrosis factor‑α (TNF‑α) alter meshwork cells, making them less efficient.

- Synechiae formation: Adhesions between the iris and cornea (posterior synechiae) can close the drainage angle permanently.

- Corticosteroid side‑effects: Steroid eye drops-commonly prescribed to calm inflammation-can themselves raise IOP, creating a paradoxical loop.

When pressure stays above the normal range (usually 10‑21 mmHg), the optic nerve fibers start to die, leading to the characteristic visual field loss of glaucoma.

Risk Factors That Make the Link Stronger

Not every uveitis patient develops glaucoma, but certain factors tip the odds:

- Duration and severity of inflammation: Chronic, recurrent uveitis poses the highest risk.

- Age: Older adults have less resilient drainage structures.

- Genetics: Family history of primary open‑angle glaucoma adds vulnerability.

- Steroid responsiveness: Some individuals' IOP spikes dramatically even with low‑dose steroids.

- Systemic disease activity: Uncontrolled autoimmune disease keeps the eye in a constant inflammatory state.

How Doctors Diagnose Inflammation‑Related Glaucoma

Diagnosis is a step‑by‑step process that blends history, imaging, and pressure checks.

- Comprehensive eye exam: Tonometry measures IOP; gonioscopy visualizes the drainage angle for synechiae.

- Slit‑lamp examination: Reveals cells in the anterior chamber (a sign of active uveitis).

- Fundus photography & OCT: Shows optic nerve head cupping and retinal nerve‑fiber‑layer thinning.

- Laboratory work‑up: Blood tests (e.g., HLA‑B27, ACE levels) and infectious panels help pinpoint the underlying cause.

- Visual field testing: Detects early peripheral vision loss typical of glaucoma.

When these clues line up-elevated IOP, optic nerve changes, and evidence of intra‑ocular inflammation-clinicians label the condition as secondary glaucoma glaucoma that occurs as a result of another eye disease, such as uveitis.

Treatment Options: Breaking the Cycle

The goal is two‑fold: soothe inflammation while keeping pressure in the safe zone.

Anti‑Inflammatory Strategies

- Corticosteroid eye drops: Powerful but monitor IOP closely; taper as soon as inflammation eases.

- Non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Topical NSAIDs (e.g., ketorolac) lessen inflammation with less impact on pressure.

- Immunomodulatory therapy: For chronic uveitis, agents like methotrexate, mycophenolate, or biologics (adalimumab) keep the immune system in check.

Pressure‑Lowering Options

- Prostaglandin analogs: First‑line drops (latanoprost, bimatoprost) increase outflow through the uveoscleral route.

- Beta‑blockers & carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Reduce aqueous production.

- Pilot‑laser trabeculoplasty (SLT): Uses low‑energy laser pulses to improve meshwork function; effective even when steroids raise pressure.

- Surgical interventions: Trabeculectomy, tube shunts, or minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) create new drainage pathways when meds fail.

Doctors often combine therapies. For example, a patient with acute anterior uveitis might start on a steroid drop plus a prostaglandin analog, then switch to a steroid‑sparing regimen once the eye calms.

Living With the Dual Diagnosis: Practical Tips

Managing eye inflammation and glaucoma isn’t just about pills-daily habits matter.

- Regular eye exams: Every 3‑6months if you have chronic uveitis; more frequent if IOP spikes.

- Protect your eyes: Wear sunglasses to reduce UV‑induced inflammation and safety glasses during risky activities.

- Adhere to medication schedules: Missing drops can let pressure rise silently.

- Watch for warning signs: New pain, halos around lights, or sudden blurry spots signal a pressure surge.

- Control systemic disease: Keep rheumatologist or internist in the loop; systemic meds often reduce eye flare‑ups.

When to Seek Immediate Care

Even with a treatment plan, some moments demand urgent attention:

- Sudden eye pain with nausea (possible acute angle‑closure glaucoma).

- Rapid vision loss or “curtain” effect across part of the field.

- Severe redness and photophobia that don’t improve after 24hours of steroids.

Prompt evaluation can preserve the remaining visual field.

Comparison: Primary Open‑Angle Glaucoma vs. Inflammation‑Related (Secondary) Glaucoma

| Feature | Primary Open‑Angle Glaucoma | Secondary (Inflammatory) Glaucoma |

|---|---|---|

| Root cause | Idiopathic drainage‑angle dysfunction | Uveitis‑induced blockage or steroid‑induced pressure rise |

| Typical age of onset | 40+ years | Any age, often younger if autoimmune disease present |

| Pressure pattern | Gradual, often < 30mmHg | Fluctuating; spikes >30mmHg common during flares |

| Response to steroids | Generally unaffected | May worsen IOP; requires careful monitoring |

| Management focus | Long‑term IOP control | Control inflammation *and* IOP |

Future Directions: Research and Emerging Therapies

Scientists are exploring ways to break the inflammation‑IOP link at a molecular level. Trials on selective cytokine inhibitors (e.g., anti‑IL‑6 antibodies) show promise in reducing both uveitis activity and steroid‑free IOP spikes. Gene‑editing approaches targeting the MYOC gene, which regulates trabecular meshwork function, could someday protect high‑risk patients before pressure climbs.

While these advances are still in labs, they underscore a growing consensus: treating eye inflammation aggressively *and* monitoring pressure hand‑in‑hand is the best strategy to prevent permanent vision loss.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can steroid eye drops cause glaucoma?

Yes. In people who are "steroid responders," pressure can rise within weeks of starting drops. Doctors usually check IOP before and during steroid therapy and may switch to non‑steroidal options if the pressure climbs.

Is eye inflammation always painful?

Not always. Anterior uveitis often hurts, but intermediate and posterior uveitis can be almost painless, presenting only with blurred vision or floaters.

How often should I get my eye pressure checked if I have uveitis?

During an active flare, check IOP at every visit (often weekly). Once the eye is quiet, most specialists recommend every 3‑6months, but the schedule may be tighter if you’ve had pressure spikes before.

Can lifestyle changes lower the risk of glaucoma linked to inflammation?

Lifestyle helps mainly by reducing systemic inflammation. Regular exercise, a balanced diet rich in omega‑3 fatty acids, and good control of autoimmune conditions can lower flare frequency, indirectly keeping eye pressure stable.

Is surgery ever needed for inflammation‑related glaucoma?

When medication and laser fail to keep IOP below 21mmHg, surgery becomes necessary. Options include trabeculectomy, tube shunts, or minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS). Successful surgery often requires the eye to be inflammation‑free beforehand.

Kelly Diglio

October 12, 2025 AT 13:31Thank you for putting together such a thorough overview of the relationship between ocular inflammation and glaucoma. The way you delineated the mechanisms-cellular debris clogging the trabecular meshwork and cytokine‑mediated dysfunction-was especially clear. I also appreciate the inclusion of the risk calculator, as it empowers patients to engage actively in their care. It’s vital for clinicians to monitor intra‑ocular pressure not only during acute uveitis flares but also during the tapering phase of steroid therapy. Your emphasis on collaboration between rheumatologists and ophthalmologists reflects best practice.

Carmelita Smith

October 16, 2025 AT 14:44I appreciate how clearly you broke down the steroid‑induced pressure spike 😊

Liam Davis

October 20, 2025 AT 15:57Indeed, the pathophysiology you described-namely, the accumulation of inflammatory cells, the release of TNF‑α, and the formation of posterior synechiae-creates a perfect storm for aqueous outflow obstruction; consequently, intra‑ocular pressure rises, and optic nerve fibers become vulnerable; therefore, routine tonometry should be incorporated into every uveitis follow‑up visit.

Arlene January

October 24, 2025 AT 17:11Spot on, Liam! 🙌 Keeping the pressure checks regular is the only way to stay ahead of the game, and patients should never feel scared to ask their doc about IOP numbers-knowledge is power!

George Embaid

October 28, 2025 AT 17:24Adding to that, it’s worth noting that systemic autoimmune control can indirectly lower ocular pressure; when the underlying disease is quiescent, the frequency of uveitic flares drops, which in turn reduces steroid exposure and IOP spikes. Sharing these insights with patients from diverse backgrounds helps build trust and adherence.

Andrea Rivarola

November 1, 2025 AT 18:37Reading through this article reminded me of how interconnected our body's systems truly are. When inflammation erupts inside the eye, the delicate drainage pathways become clogged with cellular debris, acting like tiny roadblocks that slow the aqueous humor outflow. Cytokines such as TNF‑α further alter the trabecular meshwork cells, making them less efficient at processing fluid. Over time, this obstruction leads to a gradual rise in intra‑ocular pressure, putting the optic nerve at risk. Steroid therapy, while essential for quelling the inflammation, can paradoxically exacerbate the pressure problem in people who are steroid‑responsive. That duality means clinicians must walk a tightrope, balancing anti‑inflammatory benefit against potential glaucoma risk. Regular tonometry, especially during flare‑ups and steroid tapering, becomes indispensable. Imaging techniques like OCT can catch early optic nerve changes before the patient notices any visual field loss. Moreover, systemic autoimmune diseases, such as sarcoidosis or rheumatoid arthritis, keep the immune system primed, often resulting in recurrent uveitis episodes. Managing these systemic conditions aggressively can reduce ocular flare frequency and, by extension, lower glaucoma risk. Patients should be counseled to report any new symptoms-halos around lights, sudden blurry spots, or eye pain-immediately. Lifestyle factors also play a role; a diet rich in omega‑3 fatty acids and regular exercise may help modulate systemic inflammation. Protective eyewear against UV exposure can prevent additional ocular stress. When medical therapy fails, laser trabeculoplasty or minimally invasive glaucoma surgery offer effective pressure‑lowering alternatives while preserving vision. Ultimately, the key takeaway is early detection and a holistic treatment plan that addresses both the inflammation and the pressure. By staying proactive and educated, patients can preserve their sight for years to come.

Tristan Francis

November 5, 2025 AT 19:51They don’t tell you that big pharma pushes steroid drops to keep people hooked on pricey eye meds.

Keelan Walker

November 9, 2025 AT 21:04😂 Absolutely, Keelan here! While it’s easy to get cynical, the reality is that steroids are a double‑edged sword; they calm inflammation brilliantly but can stealthily raise pressure, so regular monitoring is non‑negotiable. Lots of patients feel trapped, yet many ophthalmologists are now shifting to steroid‑sparing protocols, such as biologics or topical NSAIDs, which can preserve vision without the same risk profile. It’s a good reminder to have an open dialogue with your eye doctor about side‑effects and alternatives. 🙏

Heather Wilkinson

November 13, 2025 AT 22:17Thanks for the clear breakdown! 🌟 I’ve learned that staying on top of eye exams and protecting my eyes from UV light can really make a difference in the long run.

Henry Kim

November 17, 2025 AT 23:31Reading through the mechanisms really helped me understand why my pressure spikes after each flare; now I feel more confident asking my rheumatologist about adjusting systemic meds to keep the inflammation down.

Neha Bharti

November 22, 2025 AT 00:44Control systemic disease, control eye pressure – simple but powerful.

Samantha Patrick

November 26, 2025 AT 01:57i totally get why steroid drops can be tricky, u gotta keep checkin on that pressure.

Ryan Wilson

November 30, 2025 AT 03:11While the article is thorough, it could have mentioned that many patients still struggle to afford frequent monitoring, which is a real barrier to preventing damage.

April Conley

December 4, 2025 AT 04:24Patients need clear guidance now not later

Sophie Rabey

December 8, 2025 AT 05:37Oh great, another “glaucoma risk calculator” – because my doctor didn’t already give me a risk score on a sticky note, right?

Bruce Heintz

December 12, 2025 AT 06:51👍 Good stuff – especially the reminder that laser trabeculoplasty works even when steroids raise the pressure.

richard king

December 16, 2025 AT 08:04In the theater of the eye, inflammation plays the villain, but with the right script of anti‑inflammatories and pressure‑lowering agents, we can rewrite the tragic ending into a triumphant finale.

Dalton Hackett

December 20, 2025 AT 09:17Overall, the piece does a great job of tying together the immunologic and mechanical aspects of secondary glaucoma, and it gives readers actionable steps to discuss with their doctors.